Long associated with the visible excesses of industrialization, acid rain is often considered a problem of the past. Yet recent research shows that the phenomenon has not disappeared. It has transformed into more diffuse, more complex and often invisible atmospheric deposits. Forests, soils, freshwater systems and cultural heritage still bear the traces of this slow pollution, revealing our modern environmental legacy.

Article by Damien Lafon, royalty-free photographs.

The origins of a well documented phenomenon

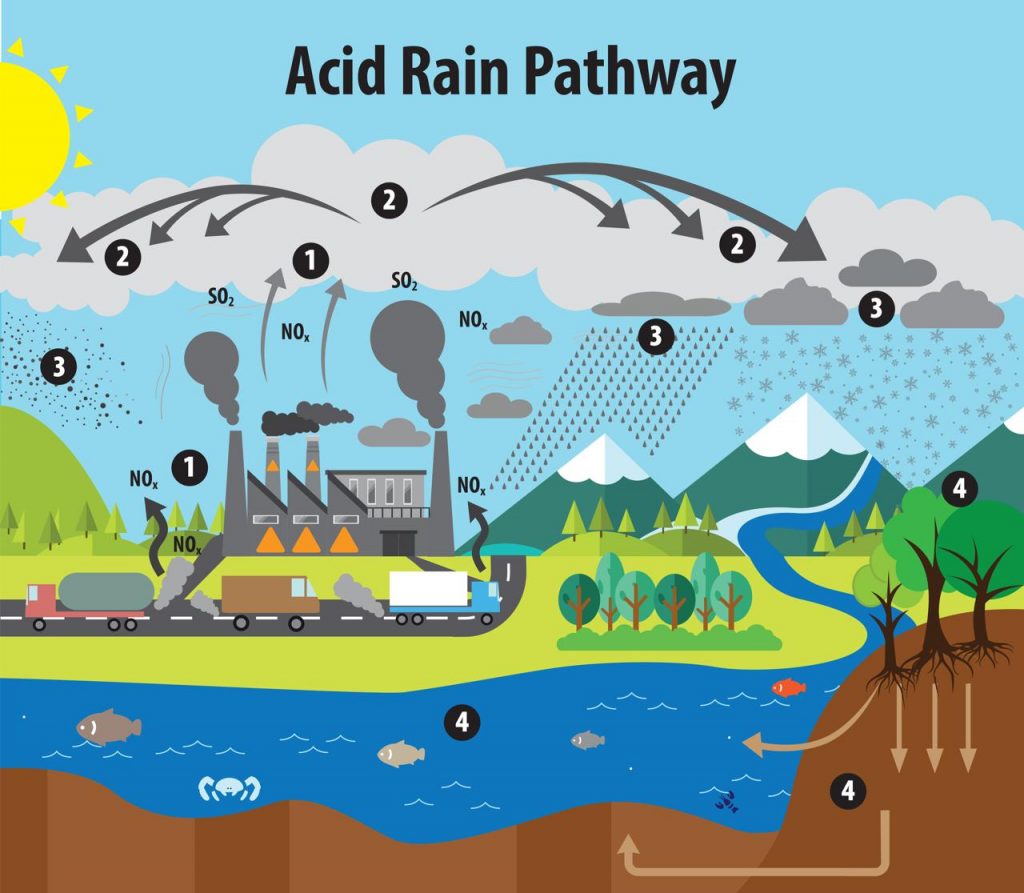

Acid rain results from the atmospheric transformation of certain gases produced by human activities. Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, released in particular through the combustion of fossil fuels, react in the atmosphere with water and oxygen. These reactions form acidic compounds that later fall back onto soils, forests and freshwater environments.

These deposits can take several forms. They may fall with rain or snow, but they can also settle as dry deposits, in the form of particles or gases. Their main effect is a gradual modification of the chemical balance of natural environments.

A real but incomplete improvement

From the late twentieth century onward, ambitious environmental policies led to a strong reduction in certain pollutant emissions. In many industrialized regions, sulfur dioxide concentrations declined significantly. Rainfall became less acidic than in previous decades.

This improvement is measurable and well documented. It allowed partial recovery in some ecosystems. However, it also contributed to the widespread belief that the problem had been resolved. Recent research shows that this perception remains incomplete.

The shift toward diffuse atmospheric deposits

While the direct acidity of rainfall has decreased in several regions, other forms of atmospheric pollution have taken over. Scientists now focus on nitrogen deposition, largely linked to intensive agriculture, livestock farming, chemical fertilizers and road traffic.

These compounds do not always cause abrupt acidification. Their defining characteristic lies in their slow and continuous accumulation. They gradually alter the chemical balance of soils and waters, often without immediate visible signs. This diffuse pollution is more difficult to detect and explain, but its long term effects are well established.

Did you know ?

In some European forests, soils remain chemically unbalanced more than thirty years after the reduction of sulfur emissions, highlighting the slow pace of recovery processes.

Forests weakened without spectacular signs

In forest ecosystems, excess nitrogen disrupts the natural balance of nutrients. Some plant species benefit from this input, while others decline. Soils gradually lose essential elements such as calcium and magnesium, leading to weakened root systems.

Trees may appear healthy while becoming more vulnerable to droughts, diseases and extreme climatic events. This silent weakening is now considered one of the major concerns among researchers.

A discreet but lasting impact on freshwater systems

Lakes and rivers are also affected by atmospheric deposits. Even when water pH remains relatively stable, chemical composition changes over time. Some aquatic species gradually disappear, replaced by organisms more tolerant of these new conditions.

This process does not always involve visible or sudden events. It is more often a slow erosion of biodiversity, difficult to perceive without long term scientific monitoring.

Cultural heritage as a chemical witness of time

Historic buildings, temples and stone sculptures offer another perspective on this transformed pollution. Calcareous materials react slowly to acidic and nitrogen based deposits. Erosion is less rapid than in the past, but it continues.

Surfaces change, details fade and micro cracks appear. Built heritage thus becomes a discreet witness to atmospheric pollution and its prolonged action over time.

Did you know ?

Today, nitrogen deposition linked to agriculture is considered by many researchers to exert greater environmental pressure than the direct acidity of rainfall in numerous regions worldwide.

Increased complexity in tropical regions

In tropical and subtropical regions, interactions between pollution, climate and human activities are even more complex. High humidity, frequent rainfall and intensive agricultural practices favor significant atmospheric deposition.

Researchers study these areas to better understand how monsoon systems, tropical soils and local emissions interact. These regions now play a key role in research on the future evolution of atmospheric deposition.

A pollution that has become invisible but persistent

The transformation of acid rain presents a major challenge for scientific communication. The phenomenon is now less visible and less dramatic, but more diffuse. Researchers refer to the chemical memory of landscapes to describe how soils, waters and ecosystems retain traces of past and present pollution.

This perspective highlights a fundamental reality. Some forms of pollution do not disappear with regulation. They transform and become embedded in territories over the long term.

Understanding the modern environmental legacy

The current challenge is no longer limited to reducing emissions, but also to understanding the chemical legacies already in place. Scientists rely on detailed analyses, long term monitoring and complex models to reconstruct these invisible trajectories.

In its current forms, acid rain becomes a powerful indicator of our relationship with the environment. It reminds us that transformations driven by human activities unfold over long timescales and continue to shape landscapes for generations.

Follow us on Instagram and Facebook to keep up to date and support our media at www.helloasso.com

This article may be of interest to you: Singapore: When Plant Towers Reinvent the City