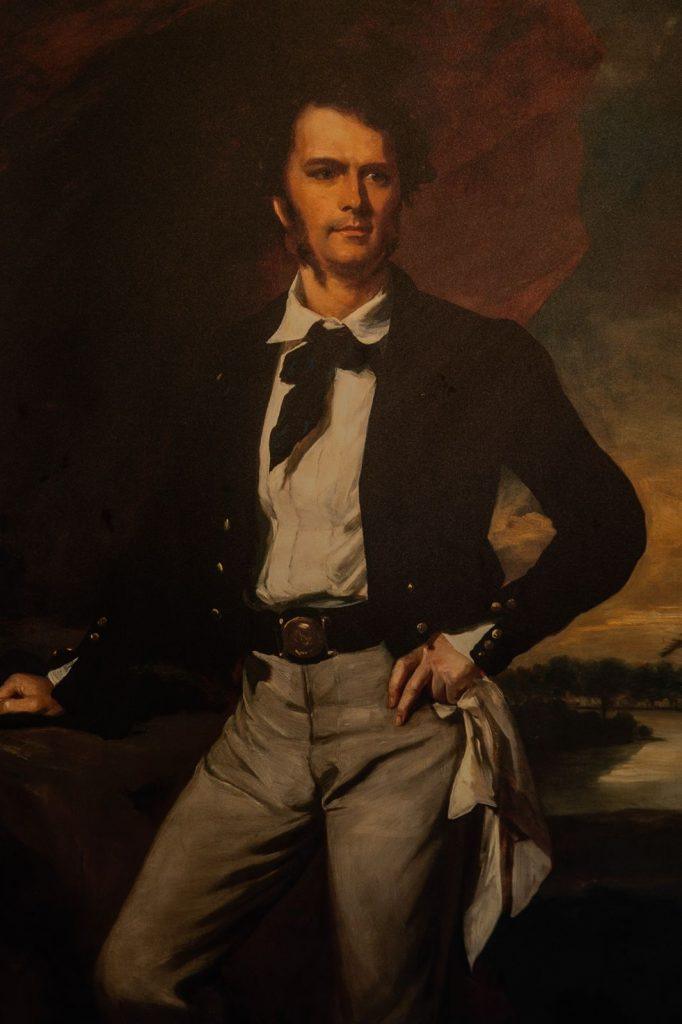

In the mid-19th century, a British adventurer with a singular destiny set foot on the shores of Sarawak. Driven by the dream of a just and peaceful kingdom, James Brooke would forever mark the history of Borneo. Today, his name remains linked to the founding of Kuching, the capital of a state born from the river and from audacity.

Article by Damien Lafon & photographs by Florian Lafon.

Origins of the White Rajah: James Brooke’s Arrival in Borneo

In 1839, a former officer of the British East India Company dropped anchor at the mouth of the Sarawak River. James Brooke, the son of an English judge, left Britain after a military career shattered by wounds and disillusionment. Asia became his horizon of exile and hope. In Borneo, he discovered a mosaic of peoples, forests, and kingdoms still little known to Europeans.

His ship, the Royalist, brought him to Kuching, then a modest village under the authority of the Sultan of Brunei. At that time, internal conflicts weakened local power. Brooke intervened, supported Dayak chiefs loyal to the sultan, and restored order. As a reward, in 1841 he received the title of Rajah of Sarawak. Thus began the legend of the “White Rajah,” a ruler from elsewhere who came to reign over a tropical land.

Sarawak: A Kingdom Born of the River and Diplomacy

The Sarawak River became the lifeblood of the new kingdom. Boats carried spices, rattan, precious timber, and the dreams of one man. James Brooke established his seat of power in Kuching and organized an administration inspired by the British model yet adapted to local realities. He surrounded himself with native advisers, supported certain Dayak leaders, and sought to pacify the tribes along the river.

His diplomacy rested on a fragile balance. He tried to curb pirate raids, common along the coast, while respecting ancestral alliances. Within a few years, Sarawak gained stability and began attracting foreign merchants. British, Dutch, and Chinese ships soon filled the bay. Kuching became a crossroads where languages, religions, and goods converged.

Did You Know?

The first flag of Sarawak, designed by Brooke himself, displayed a red cross on a yellow background. It symbolized justice and courage, two values dear to the White Rajah.

James Brooke Sarawak: Between Utopia and Authority

James Brooke saw himself as an enlightened monarch. He abolished certain forms of slavery, established a legal code, and created a local police force. Yet his kingdom rested on personal, almost paternal authority. His power relied on loyalty rather than institutions. This paternalistic vision, typical of his era, charmed London but intrigues modern historians.

His fight against piracy enhanced his reputation. In 1846, the Royal Navy supported his expeditions against the fleets of the Sulu Sea. Brooke became a hero in the Victorian press, a symbol of British courage under tropical skies. Yet massacres of local populations tarnished his glory. His dream of a “civilized” realm often hid the violent realities of conquest.

Kuching, the Capital of a Colonial Dream

Under Brooke’s reign, Kuching was transformed. Colonial-style buildings rose among the mangroves. Fort Margherita, built on the north bank of the river, guarded the city and protected it from upriver incursions. The Court House, the Astana Palace, and the first churches testified to a new era. But the city remained mixed: Chinese markets, Malay workshops, stilt houses, and Dayak longhouses formed an urban mosaic unique to Borneo.

Brooke aspired to be a ruler close to his people. He visited villages, supported missionaries, and met customary chiefs. His paternal vision also encouraged coexistence. Kuching became a living experiment where cultures met without merging.

Did You Know?

The Sarawak Museum, founded in 1891 by Charles Brooke, is the oldest in Borneo. It remains a major center for research on local cultures and biodiversity.

The Legacy of the White Rajahs: Between Memory and Controversy

After James Brooke’s death in 1868, his nephew Charles succeeded him. He continued to modernize Sarawak, building roads, schools, printing presses, and medical services. Then came Vyner Brooke, the last ruler of this unusual dynasty, who reigned until the Second World War. During the Japanese occupation, Kuching suffered hardship and fear. In 1946, the kingdom officially became a British colony. Thus ended the line of the White Rajahs, after a century of rule.

To this day, the name Brooke resonates in collective memory. Some see in him a romantic chapter of history; others, a colonial episode marked by contradictions. Museums and monuments reflect both the fascination and the complexity of this legacy.

Sarawak Today: Memory and Modernity

In Kuching, the Astana the former royal palace still houses the governor of Sarawak. Facing the river, the Brooke Gallery recounts the dynasty’s saga. Sepia portraits, old maps, and maritime relics evoke the improbable meeting between Victorian Europe and the forests of Borneo.

Yet the city is no longer that of the pioneers. Markets, mosques, and Chinese cafés animate a tranquil urban life. Its people, shaped by centuries of intermingling, form a multicultural society where Malays, Chinese, Indians, and Dayaks coexist. The spirit of openness once envisioned by Brooke lives on in a Sarawak looking to the future without denying its roots.

Did You Know?

The Astana Palace was offered by Charles Brooke to his wife Margaret as a wedding gift. The name comes from the Malay word istana, meaning “royal palace.”

Between History and Legend: The Legacy of a Dreamer

James Brooke embodies the ambiguous figure of the idealistic conqueror. He sought to civilize without colonizing, to reign without dominating. His kingdom, at the crossroads between British romanticism and the Malay world, was both a utopia and a paradox.In the shaded streets of Kuching, between spice markets and Chinese temples, his shadow still lingers a reminder of a time when one man, driven by dreams, could found a kingdom upon a river.

Follow us on Instagram and Facebook to stay informed and support our media via www.helloasso.com

This article may interest you: Kuala Lumpur: between urban verticality and living memory