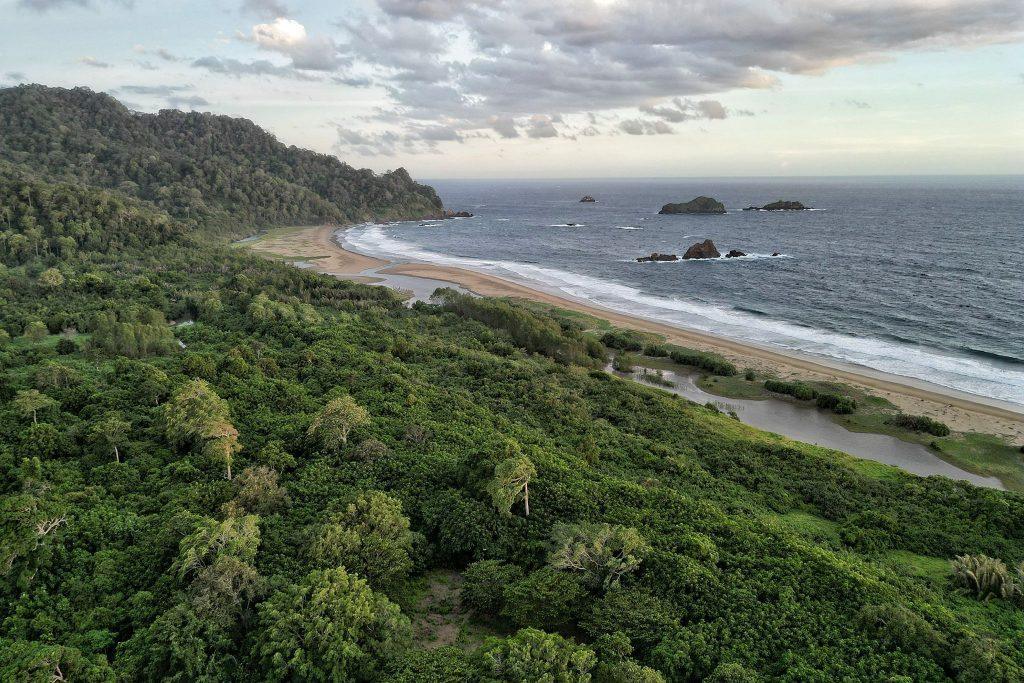

Sukamade Beach stretches like a golden ribbon beaten by the Indian Ocean. Every night, between December and March, a discreet and moving spectacle repeats itself, as it has for thousands of years: the slow ascent of green turtles coming ashore to deposit life in the sand. In the dim light of red torches, the murmur of the waves accompanies this ancestral dance. Here, nature still holds the power to astonish and to remind us of the fragility of our ecosystems.

Articles & photographs by Damien Lafon.

The Green Turtle of Java, a Voyager of the Seas

Green turtles (Chelonia mydas) sometimes travel more than 2,000 kilometers to reach the beaches of their birth. Among the oldest marine reptiles on Earth, they navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field, returning each year to the same shores to continue the cycle of life. At Sukamade, the females slowly emerge from the foam, leaving behind tracks in the sand like those of a tiny tractor. Their olive shells glisten under the stars, bearing witness to an odyssey that spans decades.

Nesting of the Green Turtles at Sukamade

When they find a suitable spot, far from lights and human noise, the turtles dig with their hind flippers a hole about fifty centimeters deep. They deposit between eighty and one hundred twenty perfectly round eggs before covering them with sand. This meticulous operation can take over an hour. Park rangers then mark the nests and protect the area from predators such as monitor lizards and stray dogs. Some eggs are moved to a protected hatchery, where hatchlings will be released into the sea a few days after emerging.

Between Local Tradition and Conservation

At Sukamade, the presence of green turtles is more than natural heritage; it shapes local life. Village families have long participated in beach surveillance, making conservation part of their daily routine. The protection program launched in the 1970s successfully combined ecotourism and preservation. Visitors can observe the nesting in small groups, guided by rangers. Strict rules apply: no white lights, no noise, and absolutely no physical contact with the animals.

Did you know?

Green turtles return to the beach where they were born, sometimes after more than thirty years. This geographical fidelity, known as philopatry, continues to fascinate scientists.

Silent Threats

Despite these efforts, the green turtle remains classified as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Plastic pollution, accidental fishing, and the destruction of nesting beaches weigh heavily on their survival. Drifting nets, in particular, cause the death of thousands every year. Along Java’s coasts, some turtles still mistake plastic bags for jellyfish. Local efforts, however commendable, cannot succeed without global awareness.

Emergence: The Race to the Sea

After fifty to sixty days of incubation, the eggs quietly crack open. Tiny turtles break through the sand, drawn by the reflection of the moon on the water. The few meters to the ocean mark their first battle for survival, as birds, crabs, and lizards lie in wait. At Sukamade, rangers often release the hatchlings at dusk to reduce losses. Only one in a thousand will reach adulthood, yet each represents a fragile and persistent hope.

Sukamade, a Natural Laboratory for Researchers

Thanks to its isolation, Sukamade Beach offers a unique research site for marine biologists. Scientists monitor migrations, identify females through tagging, and measure hatching success rates. These valuable data feed regional conservation programs across Indonesia and the wider Indian Ocean. Collaboration between local authorities, NGOs, and Indonesian universities has turned Sukamade into a model of balance between science and ecotourism. Each visitor becomes, in their own way, a witness to this rare harmony between humanity and nature.

Did you know?

The temperature of the sand determines the sex of the embryos: above 29 °C, mostly females are born. Climate change may therefore deeply disrupt future populations.

A Night at Sukamade: Awe and Responsibility

Watching a turtle lay her eggs on Sukamade Beach leaves no one untouched. The silence, the wind, and the slowness of her movements evoke a ritual scene. Beneath the moonlight, the turtle seems to entrust her future to the ocean, a quiet act of faith in life’s continuity. Yet this emotional moment also reminds us of our duty: to protect the beaches, limit plastic waste, and reduce accidental catches. Every egg buried in the sand is a fragile testament to nature’s resilience.

The Memory of the Waves

At Sukamade, every grain of sand holds the memory of generations of green turtles. Their yearly return, unbroken despite storms and threats, reminds us that harmony between humankind and the sea is still possible. Far from the crowds, this Javanese beach offers a lesson in patience and respect. In the dim red light, the turtle slowly retreats toward the ocean, leaving behind a trail that will soon fade yet its memory endures.

Follow us on Instagram and Facebook to keep up to date and support our media at www.helloasso.com

This article may be of interest to you: The Production Of Latex And Rubber In Indonesia.